Muhammad

|

A series of articles on |

|

|

Life Career Succession Interactions with Perspectives |

| This article is part of the series: |

|

| Islam |

| Beliefs |

| Allah · Oneness of God Prophets · Revealed books Angels |

| Practices |

| Profession of faith · Prayer Fasting · Charity · Pilgrimage |

| Texts and laws |

| Qur'an · Sunnah · Hadith Fiqh · Sharia · Kalam · Sufism |

| History and leadership |

| Timeline · Spread of Islam Ahl al-Bayt · Sahaba Sunni · Shi'a · Others Rashidun · Caliphate Imamate |

| Culture and society |

| Academics · Animals · Art Calendar · Children Demographics · Festivals Mosques · Philosophy Science · Women Politics · Dawah |

| Islam and other religions |

| Christianity · Judaism Hinduism · Sikhism · Jainism · Mormonism |

| See also |

| Criticism Glossary of Islamic terms |

| Islam portal |

Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullāh (Arabic: ﷴ; Transliteration: Muḥammad;[2] pronounced [mʊˈħæmmæd] (![]() listen); also spelled Muhammed or Mohammed)[3][4][5] (ca. 570/571 Mecca[مَكَةَ ]/[ مَكَهْ ] – June 8, 632),[6] was the founder of the religion of Islam [ إِسْلامْ ] and is regarded by Muslims as a messenger and prophet of God (Arabic: الله Allāh), the greatest law-bearer in a series of Islamic prophets and by most Muslims the last prophet as taught by the Qur'an 33:40–40. Muslims thus consider him the restorer of an uncorrupted original monotheistic faith (islām) of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and other prophets.[7][8][9] He was also active as a diplomat, merchant, philosopher, orator, legislator, reformer, military general, and, according to Muslim belief, an agent of divine action.[10] In Michael H. Hart's The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, Muhammad is described as the most influential person in history. Hart asserted that Muhammad was "supremely successful" in both the religious and secular realms.

listen); also spelled Muhammed or Mohammed)[3][4][5] (ca. 570/571 Mecca[مَكَةَ ]/[ مَكَهْ ] – June 8, 632),[6] was the founder of the religion of Islam [ إِسْلامْ ] and is regarded by Muslims as a messenger and prophet of God (Arabic: الله Allāh), the greatest law-bearer in a series of Islamic prophets and by most Muslims the last prophet as taught by the Qur'an 33:40–40. Muslims thus consider him the restorer of an uncorrupted original monotheistic faith (islām) of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus and other prophets.[7][8][9] He was also active as a diplomat, merchant, philosopher, orator, legislator, reformer, military general, and, according to Muslim belief, an agent of divine action.[10] In Michael H. Hart's The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, Muhammad is described as the most influential person in history. Hart asserted that Muhammad was "supremely successful" in both the religious and secular realms.

Born in 570 in the Arabian city of Mecca,[11] he was orphaned at an early age and brought up under the care of his uncle Abu Talib. He later worked mostly as a merchant, as well as a shepherd, and was first married by age 25. Discontented with life in Mecca, he retreated to a cave in the surrounding mountains for meditation and reflection. According to Islamic beliefs it was here, at age 40, in the month of Ramadan, where he received his first revelation from God. Three years after this event Muhammad started preaching these revelations publicly, proclaiming that "God is One", that complete "surrender" to Him (lit. islām) is the only way (dīn)[12] acceptable to God, and that he himself was a prophet and messenger of God, in the same vein as other Islamic prophets.[9][13][14]

Muhammad gained few followers early on, and was met with hostility from some Meccan tribes; he and his followers were treated harshly. To escape persecution, Muhammad sent some of his followers to Abyssinia before he and his remaining followers in Mecca migrated to Medina (then known as Yathrib) in the year 622. This event, the Hijra, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar, which is also known as the Hijri Calendar. In Medina, Muhammad united the conflicting tribes, and after eight years of fighting with the Meccan tribes, his followers, who by then had grown to 10,000, conquered Mecca. In 632, a few months after returning to Medina from his Farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of the Arabian Peninsula had converted to Islam; and he united the tribes of Arabia into a single Muslim religious polity.[15][16]

The revelations (or Ayat, lit. "Signs of God") — which Muhammad reported receiving until his death — form the verses of the Qur'an, regarded by Muslims as the “Word of God” and around which the religion is based. Besides the Qur'an, Muhammad’s life (sira) and traditions (sunnah) are also upheld by Muslims. They discuss Muhammad and other prophets of Islam with reverence, adding the phrase peace be upon him whenever their names are mentioned.[17] While conceptions of Muhammad in medieval Christendom and premodern times were largely negative, appraisals in modern history have been far less so.[14][18] His life and deeds have been debated and criticized by followers and opponents over the centuries.[19] He is revered as a true prophet and Manifestation of God in the Baha'i Faith.

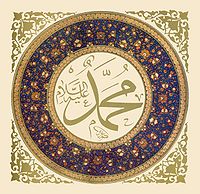

Names and appellations in the Qur'an

The name Muhammad means "Praiseworthy" and occurs four times in the Qur'an.[20] The Qur'an addresses Muhammad in the second person not by his name but by the appellations prophet, messenger, servant of God ('abd), announcer (bashir), warner (nathir), reminder (mudhakkir), witness (shahid), bearer of good tidings (mubashshir), one who calls [unto God] (dā‘ī) and the light-giving lamp (siraj munir). Muhammad is sometimes addressed by designations deriving from his state at the time of the address: thus he is referred to as the enwrapped (al-muzzammil) in Qur'an 73:1 and the shrouded (al-muddaththir) in Qur'an 74:1.[21] In the Qur'an, believers are not to distinguish between the messengers of God and are to believe in all of them (Surah 2:285). God has caused some messengers to excel above others 2:253 and in Surah 33:40 He singles out Muhammad as the "Seal of the Prophets".[22] The Qur'an also refers to Muhammad as Aḥmad "more praiseworthy" (Arabic: أحمد, Surah 61:6).

Sources for Muhammad's life

Being a highly influential historical figure, Muhammad's life, deeds, and thoughts have been debated by followers and opponents over the centuries, which makes a biography of him difficult to write.[14]

The Qur'an

Muslims regard the Qur'an as the primary source of knowledge about the historical Muhammad.[14] The Qur'an has a few allusions to Muhammad's life.[23] The Qur'an responds "constantly and often candidly to Muhammad's changing historical circumstances and contains a wealth of hidden data."[14]

Early biographies

Next in importance are the historical works by writers of the third and fourth century of the Muslim era.[24] These include the traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him (the sira and hadith literature), which provide further information on Muhammad's life.[25]

The earliest surviving written sira (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) is Ibn Ishaq's Life of God's Messenger written ca. 767 (150 AH). The work is lost, but was used verbatim at great length by Ibn Hisham and Al-Tabari.[23][26]

Another early source is the history of Muhammad's campaigns by al-Waqidi (death 207 of Muslim era), and the work of his secretary Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi (death 230 of Muslim era).[24]

Many scholars accept the accuracy of the earliest biographies, though their accuracy is unascertainable.[23] Recent studies have led scholars to distinguish between the traditions touching legal matters and the purely historical ones. In the former sphere, traditions could have been subject to invention while in the latter sphere, aside from exceptional cases, the material may have been only subject to "tendential shaping".[27]

In addition, the hadith collections are accounts of the verbal and physical traditions of Muhammad that date from several generations after his death.[28] Hadith compilations are records of the traditions or sayings of Muhammad. They might be defined as the biography of Muhammad perpetuated by the long memory of his community for their exemplification and obedience.[29]

Western academics view the hadith collections with caution as accurate historical sources.[28] Scholars such as Madelung do not reject the narrations which have been compiled in later periods, but judge them in the context of history and on the basis of their compatibility with the events and figures.[30]

Finally, there are oral traditions. Although usually discounted by historians, oral tradition plays a major role in the Islamic understanding of Muhammad.[19]

Non-Arabic sources

The earliest Greek source for Muhammed is the 9th century writer Theophanes. The earliest Syriac source is the 7th century John bar Penkaye.[31]

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula was largely arid and volcanic, making agriculture difficult except near oases or springs. The landscape was thus dotted with towns and cities, two prominent ones being Mecca and Medina. Medina was a large flourishing agricultural settlement, while Mecca was an important financial center for many surrounding tribes.[32] Communal life was essential for survival in the desert conditions, as people needed support against the harsh environment and lifestyle. Tribal grouping was encouraged by the need to act as a unit, this unity being based on the bond of kinship by blood.[33] Indigenous Arabs were either nomadic or sedentary (or bedouins), the former constantly travelling from one place to another seeking water and pasture for their flocks, while the latter settled and focused on trade and agriculture. Nomadic survival was also dependent on raiding caravans or oases, the nomads not viewing this as a crime.[34][35]

In pre-Islamic Arabia, gods or goddesses were viewed as protectors of individual tribes, their spirits being associated with sacred trees, stones, springs and wells. As well as being the site of an annual pilgrimage, the Kaaba shrine in Mecca housed 360 idol statues of tribal patron deities. Aside from these gods, the Arabs shared a common belief in a supreme deity called Allah (literally "the god"), who was remote from their everyday concerns and thus not the object of cult or ritual. Three goddesses were associated with Allah as his daughters: Allāt, Manāt and al-‘Uzzá. Monotheistic communities existed in Arabia, including Christians and Jews.[36] Hanifs – native pre-Islamic Arab monotheists – are also sometimes listed alongside Jews and Christians in pre-Islamic Arabia, although their historicity is disputed amongst scholars.[37][38] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad himself was a Hanif and one of the descendants of Ishmael, son of Abraham.[39]

Life

Life in Mecca

Muhammad was born and lived in Mecca for the first 52 years of his life (570–622) which was divided into two phases, that is before and after declaring the prophecy.

Childhood and early life

Muhammad was born in the month of Rabi' al-awwal in 570. He belonged to the Banu Hashim, one of the prominent families of Mecca, although it seems not to have been prosperous during Muhammad's early lifetime.[14][40] Tradition places the year of Muhammad's birth as corresponding with the Year of the Elephant, which is named after the failed destruction of Mecca that year by the Aksumite king Abraha who had in his army a number of elephants. Recent scholarship has suggested alternative dates for this event, such as 568 or 569.[41]

Muhammad's father, Abdullah, died almost six months before he was born.[42] According to the tradition, soon after Muhammad's birth he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert, as the desert-life was considered healthier for infants. Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, and her husband until he was two years old. Some western scholars of Islam have rejected the historicity of this tradition.[43] At the age of six Muhammad lost his mother Amina to illness and he became fully orphaned.[44] He was subsequently brought up for two years under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, of the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe. When Muhammad was eight, his grandfather also died. He now came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib, the new leader of Banu Hashim.[41] According to Watt, because of the general disregard of the guardians in taking care of weak members of the tribes in Mecca in sixth century, "Muhammad's guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seem to have been declining at that time."[45]

While still in his teens, Muhammad accompanied his uncle on trading journeys to Syria gaining experience in the commercial trade, the only career open to Muhammad as an orphan.[45] According to tradition, when Muhammad was either nine or twelve while accompanying the Meccans' caravan to Syria, he met a Christian monk or hermit named Bahira who is said to have foreseen Muhammed's career as a prophet of God.[46]

Little is known of Muhammad during his later youth, and from the fragmentary information that is available, it is hard to separate history from legend.[45] It is known that he became a merchant and "was involved in trade between the Indian ocean and the Mediterranean Sea."[47] Due to his upright character he acquired the nickname "al-Amin" (Arabic: الامين), meaning "faithful, trustworthy" and was sought out as an impartial arbitrator.[11][14][48] His reputation attracted a proposal from Khadijah, a forty-year-old widow in 595. Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.[47]

Wives and children

Muhammad's life is traditionally defined into two periods: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca (from 570 to 622), and post-hijra in Medina (from 622 until 632). Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives or concubines (there are differing accounts on the status of some of them as wife or concubine[49])[50] All but two of his marriages were contracted after the migration to Medina.

Part of a series on Islam Umm-al-Momineen Wives of Muhammad |

|---|

|

Sawda bint Zama Hafsa bint Umar Zaynab bint Khuzayma Hind bint Abi Umayya Zaynab bint Jahsh Juwayriya bint al-Harith Ramlah bint Abi Sufyan Rayhana bint Zayd Safiyya bint Huyayy Maymuna bint al-Harith Maria al-Qibtiyya |

At the age of 25, Muhammad married the wealthy Khadijah bint Khuwaylid. The marriage lasted for 25 years and was a happy one.[51] Muhammad relied upon Khadija in many ways and did not enter into marriage with another woman during this marriage.[52][53] After the death of Khadija, it was suggested to Muhammad by Khawla bint Hakim that he should marry Sawda bint Zama, a Muslim widow, or Aisha, daughter of Um Ruman and Abu Bakr of Mecca. Muhammad is said to have asked her to arrange for him to marry both.[54] Traditional sources dictate that Aisha was six or seven years old when betrothed to Muhammad[54][55][56] but the marriage was not consummated until she was nine or ten years old.[54][55][57][58][59] Later, Muhammad married additional wives, nine of whom survived him.[50] Aisha, who became known as Muhammad's favourite wife in Sunni tradition, survived him by many decades and was instrumental in helping to bring together the scattered sayings of Muhammad that would form the Hadith literature for the Sunni branch of Islam.[54]

After migration to Medina, Muhammad (who was now in his fifties) married several women. These marriages were contracted mostly for political or humanitarian reasons, these wives being either widows of Muslims who had been killed in the battles and had been left without a protector, or belonging to important families or clans whom it was necessary to honor and strengthen alliances.[60]

Muhammad did his own household chores and helped with housework, such as preparing food, sewing clothes and repairing shoes. Muhammad is also said to have had accustomed his wives to dialogue; he listened to their advice, and the wives debated and even argued with him.[61][62][63]

Khadijah is said to have borne Muhammad four daughters (Ruqayyah bint Muhammad, Umm Kulthum bint Muhammad, Zainab bint Muhammad, Fatimah Zahra) and two sons (Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad and Qasim ibn Muhammad) who both died in childhood. All except two of his daughters, Fatimah and Zainab, died before him.[64] Shi'a scholars contend that Fatimah was Muhammad's only daughter.[65] Maria al-Qibtiyya bore him a son named Ibrahim ibn Muhammad, but the child died when he was two years old.[64]

Muhammad's descendants through Fatimah are known as sharifs, syeds or sayyids. These are honorific titles in Arabic, sharif meaning 'noble' and sayed or sayyid meaning 'lord' or 'sir'. As Muhammad's only descendants, they are respected by both Sunni and Shi'a, though the Shi'as place much more emphasis and value on their distinction.[66]

Beginnings of the Qur'an

At some point Muhammad adopted the practice of meditating alone for several weeks every year in a cave on Mount Hira near Mecca.[67][68] Islamic tradition holds that during one of his visits to Mount Hira, the angel Gabriel appeared to him in the year 610 and commanded Muhammad to recite the following verses:[69]

Proclaim! (or read!) in the name of thy Lord and Cherisher, Who created- Created man, out of a (mere) clot of congealed blood: Proclaim! And thy Lord is Most Bountiful,- He Who taught (the use of) the pen,- Taught man that which he knew not.(Qur'an 96:1-5)

According to some traditions, upon receiving his first revelations Muhammad was deeply distressed.[70]. When returned home, Muhammad was consoled and reassured by his wife, Khadijah and her Christian cousin, Waraqah ibn Nawfal. Shia tradition maintains that Muhammad was neither surprised nor frightened at the appearance of Gabriel but rather welcomed him as if he had been expecting him.[71] The initial revelation was followed by a pause of three years during which Muhammad gave himself up further to prayers and spiritual practices. When the revelations resumed he was reassured and commanded to begin preaching: Your lord has not forsaken you nor does he hate [you] (Qur'an 93:1-11).[72][73]

According to Welch these revelations were accompanied by mysterious seizures, and the reports are unlikely to have been forged by later Muslims.[14] Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages.[74] According to the Qur'an, one of the main roles of Muhammad is to warn the unbelievers of their eschatological punishment (Qur'an 38:70, Qur'an 6:19). Sometimes the Qur'an does not explicitly refer to the Judgment day but provides examples from the history of some extinct communities and warns Muhammad's contemporaries of similar calamities (Qur'an 41:13–16).[21] Muhammad is not only a warner to those who reject God's revelation, but also a bearer of good news for those who abandon evil, listen to the divine word and serve God.[75] Muhammad's mission also involves preaching monotheism: The Qur'an demands Muhammad to proclaim and praise the name of his Lord and instructs him not to worship idols apart from God or associate other deities with God.[21]

The key themes of the early Qur'anic verses included the responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of dead, God's final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in hell and pleasures in Paradise; and the signs of God in all aspects of life. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not to kill newborn girls.[14]

Opposition

|

|||||

According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.[76] She was soon followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zaid.[76] Around 613, Muhammad began his public preaching (Qur'an 26:214).[77] Most Meccans ignored him and mocked him, while a few others became his followers. There were three main groups of early converts to Islam: younger brothers and sons of great merchants; people who had fallen out of the first rank in their tribe or failed to attain it; and the weak, mostly unprotected foreigners.[78]

According to Ibn Sad, the opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that condemned idol worship and the Meccan forefathers who engaged in polytheism.[79] However, the Qur'anic exegesis maintains that it began as soon as Muhammad started public preaching.[80] As the number of followers increased, he became a threat to the local tribes and the rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life, which Muhammad threatened to overthrow. Muhammad’s denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, the Quraysh, as they were the guardians of the Ka'aba.[78] The powerful merchants tried to convince Muhammad to abandon his preaching by offering him admission into the inner circle of merchants, and establishing his position therein by an advantageous marriage. However, he refused.[78]

Tradition records at great length the persecution and ill-treatment of Muhammad and his followers.[14] Sumayyah bint Khabbab, a slave of Abu Jahl and a prominent Meccan leader, is famous as the first martyr of Islam, having been killed with a spear by her master when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal, another Muslim slave, was tortured by Umayyah ibn Khalaf who placed a heavy rock on his chest to force his conversion.[81][82] Apart from insults, Muhammad was protected from physical harm as he belonged to the Banu Hashim clan.[83][84]

In 615, some of Muhammad's followers emigrated to the Ethiopian Aksumite Empire and founded a small colony there under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian emperor Aṣḥama ibn Abjar.[14]

An early hadith known as "The Story of the Cranes" (translation: قصة الغرانيق, transliteration: Qissat al Gharaneeq) was propagated by two Islamic scholars, Ibn Kathir al Dimashqi and Ibn Hijir al Masri, where the former has strengthened it and the latter called it fabricated[85] (see Science of hadith). The hadith describes Muhammad's involvement at the time of migration in an episode which historian William Muir called the "Satanic Verses". The account holds that Muhammad pronounced a verse acknowledging the existence of three Meccan goddesses considered to be the daughters of Allah, praising them, and appealing for their intercession. According to this account, Muhammad later retracted the verses at the behest of Gabriel.[86] Islamic scholars have weakened the hadith[87] and have denied the historicity of the incident as early as the tenth century.[88] In any event, relations between the Muslims and their pagan fellow-tribesmen were already deteriorated and worsening.

In 617 the leaders of Makhzum and Banu Abd-Shams, two important Quraysh clans, declared a public boycott against Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, to pressurize it into withdrawing its protection of Muhammad. The boycott lasted three years but eventually collapsed as it failed in its objective.[89][90]

Sunnah

The Sunnah represents the actions and sayings of Muhammad (preserved in reports known as Hadith), and covers a broad array of activities and beliefs ranging from religious rituals, personal hygiene, burial of the dead to the mystical questions involving the love between humans and God. The Sunnah is considered a model of emulation for pious Muslims and has to a great degree influenced the Muslim culture. The greeting that Muhammad taught Muslims to offer each other, “may peace be upon you” (Arabic: as-salamu `alaykum) is used by Muslims throughout the world. Many details of major Islamic rituals such as daily prayers, the fasting and the annual pilgrimage are only found in the Sunnah and not the Qur'an.[91]

The Sunnah also played a major role in the development of the Islamic sciences. It contributed much to the development of Islamic law, particularly from the end of the first Islamic century.[92] Muslim mystics, known as sufis, who were seeking for the inner meaning of the Qur'an and the inner nature of Muhammad, viewed the prophet of Islam not only as a prophet but also as a perfect saint. Sufi orders trace their chain of spiritual descent back to Muhammad.[93]

Isra and Mi'raj

Islamic tradition relates that in 620, Muhammad experienced the Isra and Mi'raj, a miraculous journey said to have occurred with the angel Gabriel in one night. In the first part of the journey, the Isra, he is said to have travelled from Mecca on a winged horse to "the farthest mosque" (in Arabic: masjid al-aqsa), which Muslims usually identify with the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. In the second part, the Mi'raj, Muhammad is said to have toured heaven and hell, and spoken with earlier prophets, such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.[94] Ibn Ishaq, author of the first biography of Muhammad, presents this event as a spiritual experience whereas later historians like Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir present it as a physical journey.[94]

When he was transported to Heaven, he reported seeing an angel with "70,000 heads, each head having 70,000 mouths, each mouth having 70,000 tongues, each tongue speaking 70,000 languages; and every one involved in singing God's (Allah's) praises." After calculation this would mean the angel spoke 24 quintillion (2.401 × 1019) languages for the praise of Allah. This description is similar word for word to the description of an angel seen by Moses in "The Revelation of Moses" [95]

Some western scholars of Islam hold that the oldest Muslim tradition identified the journey as one traveled through the heavens from the sacred enclosure at Mecca to the celestial al-Baytu l-Maʿmur (heavenly prototype of the Kaaba); but later tradition identified Muhammad's journey from Mecca to Jerusalem.[96]

| Timeline of Muhammad in Medina | |

|---|---|

| Important dates and locations in the life of Muhammad in Medina | |

| c. 618 | Medinan Civil War |

| 622 | Emigrates to Medina (Hijra) |

| 622 | Ascension to heaven |

| 624 | Battle of Badr: Muslims defeat Makkahs |

| 624 | Expulsion of Banu Qaynuqa |

| 625 | Battle of Uhud: Makkahs defeat Muslims |

| 625 | Expulsion of Banu Nadir |

| 627 | Battle of the Trench |

| 627 | Demise of Banu Qurayza |

| 628 | Treaty of Hudaybiyyah |

| c. 628 | Gains access to Makkah shrine Kaaba |

| 628 | Conquest of the Khaybar oasis |

| 629 | First hajj pilgrimage |

| 629 | Attack on Byzantine Empire fails: Battle of Mu'tah |

| 630 | Bloodless conquest of Mecca |

| c. 630 | Battle of Hunayn |

| c. 630 | Siege of Ta'if |

| c. 631 | Rules most of the Arabian peninsula |

| c. 632 | Attacks the Ghassanids: Tabuk |

| 632 | Farewell hajj pilgrimage |

| 632 | Death (June 8): Medina |

Hijra

Migration to Medina

A delegation consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad as a neutral outsider to Medina to serve as chief arbitrator for the entire community.[97][98] There was fighting in Yathrib mainly involving its Arab and Jewish inhabitants for around a hundred years before 620.[97] The recurring slaughters and disagreements over the resulting claims, especially after the Battle of Bu'ath in which all clans were involved, made it obvious to them that the tribal conceptions of blood-feud and an eye for an eye were no longer workable unless there was one man with authority to adjudicate in disputed cases.[97] The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.[14]

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina until virtually all his followers left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure of Muslims, according to the tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassinate Muhammad. With the help of Ali, Muhammad fooled the Meccans who were watching him, and secretly slipped away from the town with Abu Bakr.[99] By 622, Muhammad emigrated to Medina, a large agricultural oasis. Those who migrated from Mecca along with Muhammad became known as muhajirun (emigrants).[14]

Establishment of a new polity

Among the first things Muhammad did in order to settle down the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was drafting a document known as the Constitution of Medina, "establishing a kind of alliance or federation" among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca, which specified the rights and duties of all citizens and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including that of the Muslim community to other communities, specifically the Jews and other "Peoples of the Book").[97][98] The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, Ummah, had a religious outlook but was also shaped by practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes.[14] It effectively established the first Islamic state.

The first group of pagan converts to Islam in Medina were the clans who had not produced great leaders for themselves but had suffered from warlike leaders from other clans. This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Medina, apart from some exceptions. According to Ibn Ishaq, this was influenced by the conversion of Sa'd ibn Mu'adh (a prominent Medinan leader) to Islam.[100] Those Medinans who converted to Islam and helped the Muslim emigrants find shelter became known as the ansar (supporters).[14] Then Muhammad instituted brotherhood between the emigrants and the supporters and he chose Ali as his own brother.[101]

Beginning of armed conflict

Following the emigration, the Meccans seized the properties of the Muslim emigrants in Mecca.[102] Economically uprooted and with no available profession, the Muslim migrants turned to raiding Meccan caravans as an act of war, deliberately initiating armed conflict between the Muslims and Mecca.[103][104] Muhammad delivered Qur'anic verses permitting the Muslims to fight the Meccans (see Qur'an 22:39–40).[105] These attacks pressured Mecca by interfering with trade, and allowed the Muslims to acquire wealth, power and prestige while working towards their ultimate goal of inducing Mecca's submission to the new faith.[106][107] In March of 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for them at Badr.[108] Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded the Muslims. Meanwhile, a force from Mecca was sent to protect the caravan, continuing forward to confront the Muslims upon hearing that the caravan was safe. The Battle of Badr began in March of 624.[109] Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans with only fourteen Muslims dead. They also succeeded in killing many Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl.[110] Seventy prisoners had been acquired, many of whom were soon ransomed in return for wealth or freed.[103][111][112] Muhammad and his followers saw in the victory a confirmation of their faith.[14] The Qur'anic verses of this period, unlike the Meccan ones, dealt with practical problems of government and issues like the distribution of spoils.[113]

The victory strengthened Muhammad's position in Medina and dispelled earlier doubts among his followers. As a result the opposition to him became less vocal. Pagans who had not yet converted were very bitter about the advance of Islam. Two persons, Asma bint Marwan and Abu 'Afak had composed verses taunting and insulting the Muslims. They were killed by persons belonging to their own or related clans , but nothing was said and no blood-feud followed.[114]

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of three main Jewish tribes.[14] Following the Battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hijaz.[14]

Conflict with Mecca

The attack at Badr committed Muhammad to total war with Meccans, who were now anxious to avenge their defeat. To maintain their economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been lost at Badr.[115] In the ensuing months, Muhammad led expeditions on tribes allied with Mecca and sent out a raid on a Meccan caravan.[116] Abu Sufyan subsequently gathered an army of three thousand men and set out for an attack on Medina.[117]

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army's presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, there was dispute over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many senior figures suggested that it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of its heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying their crops, and that huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the wishes of the latter, and readied the Muslim force for battle. Thus, Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (where the Meccans had camped) and fought the Battle of Uhud on March 23.[118][119] Although the Muslim army had the best of the early encounters, indiscipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat, with 75 Muslims killed including Hamza, Muhammad's uncle and one of the best known martyrs in the Muslim tradition. The Meccans did not pursue the Muslims further, but marched back to Mecca declaring victory. They were not entirely successful, however, as they had failed to achieve their aim of completely destroying the Muslims.[120][121] The Muslims buried the dead, and returned to Medina that evening. Questions accumulated as to the reasons for the loss, and Muhammad subsequently delivered Qur'anic verses [Qur'an 3:152] which indicated that their defeat was partly a punishment for disobedience and partly a test for steadfastness.[122]

Abu Sufyan now directed his efforts towards another attack on Medina. He attracted the support of nomadic tribes to the north and east of Medina, using propaganda about Muhammad's weakness, promises of booty, memories of the prestige of the Quraysh and use of bribes.[123] Muhammad's policy was now to prevent alliances against him as much as he could. Whenever alliances of tribesmen against Medina were formed, he sent out an expedition to break them up.[123] When Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Medina, he reacted with severity.[124] One example is the assassination of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, a chieftain of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir who had gone to Mecca and written poems that helped rouse the Meccans' grief, anger and desire for revenge after the Battle of Badr.[125] Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Banu Nadir from Medina.[126] Muhammad's attempts to prevent formation of a confederation against him were unsuccessful, though he was able to increase his own forces and stop many potential tribes from joining his enemies.[127]

Siege of Medina

With the help of the exiled Banu Nadir, the Quraysh military leader Abu Sufyan had mustered a force of 10,000 men. Muhammad prepared a force of about 3000 men and adopted a new form of defense unknown in Arabia at that time: the Muslims dug a trench wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman the Persian. The siege of Medina began on March 31 627 and lasted for two weeks.[128] Abu Sufyan's troops were unprepared for the fortifications they were confronted with, and after an ineffectual siege lasting several weeks, the coalition decided to go home.[129] The Qur'an discusses this battle in verses Qur'an 33:9-33:27.[80] During the battle, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza, located at the south of Medina, had entered into negotiations with Meccan forces to revolt against Muhammad. Although they were swayed by suggestions that Muhammad was sure to be overwhelmed, they desired reassurance in case the confederacy was unable to destroy him. No agreement was reached after the prolonged negotiations, in part due to sabotage attempts by Muhammad's scouts.[130] After the coalition's retreat, the Muslims accused the Banu Qurayza of treachery and besieged them in their forts for 25 days. The Banu Qurayza eventually surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were beheaded, while the women and children were enslaved.[131][132] In the siege of Medina, the Meccans exerted their utmost strength towards the destruction of the Muslim community. Their failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria was gone.[133] Following the Battle of the Trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north which ended without any fighting.[14] While returning from one of these (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad's wife. Aisha was exonerated from the accusations when Muhammad announced that he had received a revelation confirming Aisha's innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses.[54]

Truce of Hudaybiyyah

Although Muhammad had already delivered Qur'anic verses commanding the Hajj,[134] the Muslims had not performed it due to the enmity of the Quraysh. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to make preparations for a pilgrimage (umrah) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision where he was shaving his head after the completion of the Hajj.[135] Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just outside of Mecca.[136] According to Watt, although Muhammad's decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream, he was at the same time demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam does not threaten the prestige of their sanctuary, and that Islam was an Arabian religion.[136]

Negotiations commenced with emissaries going to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Acceptance" (Arabic: بيعة الرضوان , bay'at al-ridhwān) or the "Pledge under the Tree". News of Uthman's safety, however, allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh.[136][137] The main points of the treaty included the cessation of hostilities; the deferral of Muhammad's pilgrimage to the following year; and an agreement to send back any Meccan who had gone to Medina without the permission of their protector.[136]

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the terms of the treaty. However, the Qur'anic sura "Al-Fath" (The Victory) (Qur'an 48:1-29) assured the Muslims that the expedition from which they were now returning must be considered a victorious one.[138] It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty. According to Welch, these benefits included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity posing well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.[14]

After signing the truce, Muhammad made an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar, known as the Battle of Khaybar. This was possibly due to it housing the Banu Nadir, who were inciting hostilities against Muhammad, or to regain some prestige to deflect from what appeared to some Muslims as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya.[117][139] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers of the world, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date is given variously in the sources).[14][140][141] Hence he sent messengers (with letters) to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Khosrau of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others.[140][141] In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad sent his forces against the Arabs on Transjordanian Byzantine soil in the Battle of Mu'tah, in which the Muslims were defeated.[142]

Final years

Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyyah had been enforced for two years.[143][144] The tribe of Banu Khuza'a had good relations with Muhammad, whereas their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had an alliance with the Meccans.[143][144] A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuza'a, killing a few of them.[143][144] The Meccans helped the Banu Bakr with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting.[143] After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were that either the Meccans paid blood money for those slain among the Khuza'ah tribe; or, that they should disavow themselves of the Banu Bakr; or, that they should declare the truce of Hudaybiyyah null.[145]

The Meccans replied that they would accept only the last condition.[145] However, soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Sufyan to renew the Hudaybiyyah treaty, but now his request was declined by Muhammad.

Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[146] In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with an enormous force, said to number more than ten thousand men. With minimal casualties, Muhammad took control of Mecca.[147] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who had mocked and ridiculed him in songs and verses. Some of these were later pardoned.[148] Most Meccans converted to Islam and Muhammad subsequently destroyed all the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba.[149][150] The Qur'an discusses the conquest of Mecca.[80][151]

Conquest of Arabia

Soon after the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were collecting an army twice the size of Muhammad's. The Banu Hawazin were old enemies of the Meccans. They were joined by the Banu Thaqif (inhabiting the city of Ta'if) who adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans.[152] Muhammad defeated the Hawazin and Thaqif tribes in the Battle of Hunayn.[14]

In the same year, Muhammad made the expedition of Tabuk against northern Arabia because of their previous defeat at the Battle of Mu'tah as well as reports of the hostile attitude adopted against Muslims. Although Muhammad did not make contact with hostile forces at Tabuk, he received the submission of some local chiefs of the region.[14][153]

A year after the Battle of Tabuk, the Banu Thaqif sent emissaries to Medina to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many bedouins submitted to Muhammad in order to be safe against his attacks and to benefit from the booties of the wars.[14] However, the bedouins were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain their independence, their established code of virtue and their ancestral traditions. Muhammad thus required of them a military and political agreement according to which they "acknowledge the suzerainty of Medina, to refrain from attack on the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religious levy."[154]

Last years in Mecca

Muhammad's wife Khadijah and his uncle Abu Talib both died in 619, the year thus being known as the "year of sorrow". With the death of Abu Talib, the leadership of the Banu Hashim clan was passed to Abu Lahab, an inveterate enemy of Muhammad. Soon afterwards, Abu Lahab withdrew the clan's protection from Muhammad. This placed Muhammad in danger of death since the withdrawal of clan protection implied that the blood revenge for his killing would not be exacted. Muhammad then visited Ta'if, another important city in Arabia, and tried to find a protector for himself there, but his effort failed and further brought him into physical danger.[14][90] Muhammad was forced to return to Mecca. A Meccan man named Mut'im b. Adi (and the protection of the tribe of Banu Nawfal) made it possible for him safely to re-enter his native city.[14][90]

Many people were visiting Mecca on business or as pilgrims to the Kaaba. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina).[14] The Arab population of Yathrib were familiar with monotheism because a Jewish community existed there.[14] Converts to Islam came from nearly all Arab tribes in Medina, such that by June of the subsequent year there were seventy-five Muslims coming to Mecca for pilgrimage and to meet Muhammad. Meeting him secretly by night, the group made what was known as the "Second Pledge of al-`Aqaba", or the "Pledge of War"[155] Following the pledges at Aqabah, Muhammad encouraged his followers to emigrate to Yathrib. As with the migration to Abyssinia, the Quraysh attempted to stop the emigration. However, almost all Muslims managed to leave.[156]

Farewell pilgrimage and death

At the end of the tenth year after the migration to Medina, Muhammad carried through his first truly Islamic pilgrimage, thereby teaching his followers the rites of the annual Great Pilgrimage (Hajj).[14]

After completing the pilgrimage, Muhammad delivered a famous speech known as The Farewell Sermon. In this sermon, Muhammad advised his followers not to follow certain pre-Islamic customs such as adding intercalary months to align the lunar calendar with the solar calendar. Muhammad abolished all old blood feuds and disputes based on the former tribal system and asked for all old pledges to be returned as implications of the creation of the new Islamic community. Commenting on the vulnerability of women in his society, Muhammed asked his male followers to “Be good to women; for they are powerless captives (awan) in your households. You took them in God’s trust, and legitimated your sexual relations with the Word of God, so come to your senses people, and hear my words ...”. He also told them that they were entitled to discipline their wives but should do so with kindness. Muhammad also addressed the issue of inheritance by forbidding false claims of paternity or of a client relationship to the deceased and also forbidding his followers to leave their wealth to a testamentary heir. He also upheld the sacredness of four lunar months in each year.[157][158] According to Sunni tafsir, the following Qur'anic verse was delivered in this incident: “Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you.”(Qur'an 5:3)[14] According to Shia tafsir, it refers to appointment of Ali ibn Abi Talib at the pond of Khumm as Muhammad's successor, this occurring a few days later when Muslims were returning from Mecca to Medina.[159]

A few months after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with head pain and weakness. He died on Monday, June 8, 632, in Medina, at the age of 63.[160] With his head resting on Aisha's lap he murmured his final words soon after asking her to dispose of his last worldly goods, which were seven coins:

Rather, God on High and paradise.[160]—Muhammad

He is buried where he died, which was in Aisha's house and is now housed within the Mosque of the Prophet in the city of Medina.[14][161][162] Next to Muhammad's tomb, there is another empty tomb that Muslims believe awaits Jesus.[162][163]

Aftermath

Muhammad united the tribes of Arabia into a singular Arab Muslim religious polity in the last years of his life. With Muhammad's death, disagreement broke out over who would succeed him as leader of the Muslim community.[16] Umar ibn al-Khattab, a prominent companion of Muhammad, nominated Abu Bakr, Muhammad's friend and collaborator. Others added their support and Abu Bakr was made the first caliph. This choice was disputed by some of Muhammad's companions, who held that Ali ibn Abi Talib, his cousin and son-in-law, had been designated the successor by Muhammad at Ghadir Khumm. Abu Bakr's immediate task was to make an expedition against the Byzantine (or Eastern Roman Empire) forces because of the previous defeat, although he first had to put down a rebellion by Arab tribes in an episode referred to by later Muslim historians as the Ridda wars, or "Wars of Apostasy".[164]

The pre-Islamic Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sassanian empires. The Roman-Persian Wars between the two had devastated the inhabitants, making the empires unpopular amongst local tribes. Furthermore, most Christian Churches in the lands to be conquered by Muslims such as Nestorians, Monophysites, Jacobites and Copts were under pressure from the Christian Orthodoxy who deemed them heretics. Within only a decade, Muslims conquered Mesopotamia and Persia, Roman Syria and Roman Egypt.[165] and established the Rashidun empire.

Early reforms under Islam

According to William Montgomery Watt, for Muhammad, religion was not a private and individual matter but rather “the total response of his personality to the total situation in which he found himself. He was responding [not only]… to the religious and intellectual aspects of the situation but also to the economic, social, and political pressures to which contemporary Mecca was subject."[166] Bernard Lewis says that there are two important political traditions in Islam – one that views Muhammad as a statesman in Medina, and another that views him as a rebel in Mecca. He sees Islam itself as a type of revolution that greatly changed the societies into which the new religion was brought.[167]

Historians generally agree that Islamic social reforms in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery and the rights of women and children improved on the status quo of Arab society.[167][168] For example, according to Lewis, Islam "from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents".[167] Muhammad's message transformed the society and moral order of life in the Arabian Peninsula through reorientation of society as regards to identity, world view, and the hierarchy of values.[169] Economic reforms addressed the plight of the poor, which was becoming an issue in pre-Islamic Mecca.[170] The Qur'an requires payment of an alms tax (zakat) for the benefit of the poor, and as Muhammad's position grew in power he demanded that those tribes who wanted to ally with him implement the zakat in particular.[171][172]

Slaves

The Qur'an considers emancipation of a slave to be a highly meritorious deed, or as a condition of repentance for many sins. Therefore Muhammad was the owner of slaves, whom he bought usually to free[173], including concubines (although this claim is disputed) [174], a wetnurse, and one slave he bought, freed and adopted as his son (Zayd).[175] However, Muhammad himself did not ban slavery.

Legacy

Muslim views

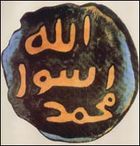

Following the attestation to the oneness of God, the belief in Muhammad's prophethood is the main aspect of the Islamic faith. Every Muslim proclaims in the Shahadah that "I testify that there is no God but Allah, and I testify that Muhammad is a messenger of Allah". The Shahadah is the basic creed or tenet of Islam. Ideally, it is the first words a newborn will hear, and children are taught as soon as they are able to understand it and it will be recited when they die. Muslims must repeat the shahadah in the call to prayer (adhan) and the prayer itself. Non-Muslims wishing to convert to Islam are required to recite the creed.[177]

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad's life, his intercession and of his miracles (particularly "Splitting of the moon") have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry. The Qur'an refers to Muhammad as "a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds" (Qur'an 21:107).[14] The association of rain with mercy in Oriental countries has led to imagining Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessings and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth (see, for example, the Sindhi poem of Shah ʿAbd al-Latif).[14] Muhammad's birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Islamic world, excluding Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged.[178] Muslims experience Muhammad as a living reality, believing in his ongoing significance to human beings as well as animals and plants.[178] When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad or any other prophet in Islam, they usually follow it with Peace be upon him (Arabic: sallAllahu `alayhi wa sallam) like "Muhammad (Peace be upon him)".[17]

According to the Qur'an, Muhammad is only the last of a series of Prophets sent by Allah for the benefit of mankind, and thus commands Muslims to make no distinction between them and to surrender to one God Allah. Qur'an 10:37–37 states that "...it (the Qur'an) is a confirmation of (revelations) that went before it, and a fuller explanation of the Book - wherein there is no doubt - from The Lord of the Worlds.". Similarly Qur'an 46:12–12 states "...And before this was the book of Moses, as a guide and a mercy. And this Book confirms (it)...", while Qur'an 2:136–136 commands the believers of Islam to "Say: we believe in God and that which is revealed unto us, and that which was revealed unto Abraham and Ishmael and Isaac and Jacob and the tribes, and that which Moses and Jesus received, and which the prophets received from their Lord. We make no distinction between any of them, and unto Him we have surrendered."

Historian Denis Gril believes that the Qur'an does not overtly describe Muhammad performing miracles, and the supreme miracle of Muhammad is finally identified with the Qur’an itself.[179] However, Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several supernatural events.[180] For example, many Muslim commentators and some Western scholars have interpreted the Surah 54:1-2 as referring to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh when they began persecuting his followers.[179][181]

Other views

Non-Muslim views regarding Muhammad have ranged across a large spectrum of responses and beliefs, many of which have changed over time.[182][183]

European and Western views

The learned circles of Middle Ages Europe—primarily Latin-literate scholars—had fairly extensive, concrete biographical knowledge about the life of Muhammad, though they interpreted that information through a Christian religious lens that viewed Muhammad as a charlatan driven by ambition and eagerness for power, and who seduced the Saracens into his submission under a religious guise.[14] Popular European literature of the time lacked even this knowledge, and portrayed Muhammad as though he were worshipped by Muslims in the manner of an idol or a heathen god.[14] Some medieval Christians believed he died in 666, alluding to the number of the beast, instead of his actual death date in 632;[184] others changed his name from Muhammad to Mahound, the "devil incarnate".[185] Bernard Lewis writes "The development of the concept of Mahound started with considering Muhammad as a kind of demon or false god worshipped with Apollyon and Termagant in an unholy trinity."[186] A later medieval work, Livre dou Tresor represents Muhammad as a former monk and cardinal.[14] Dante's Divine Comedy (Canto XXVIII), puts Muhammad, together with Ali, in Hell "among the sowers of discord and the schismatics, being lacerated by devils again and again."[14] Cultural critic and author Edward Said wrote in Orientalism regarding Dante's depiction of Muhammad:

Empirical data about the Orient...count for very little; ... What ... Dante tried to do in the Inferno, is ... to characterize the Orient as alien and to incorporate it schematically on a theatrical stage whose audience, manager, and actors are ... only for Europe. Hence the vacillation between the familiar and the alien; Mohammed is always the imposter (familiar, because he pretends to be like the Jesus we know) and always the Oriental (alien, because although he is in some ways "like" Jesus, he is after all not like him).[187]

After the reformation, Muhammad was no longer viewed by Christians as a god or idol, but as a cunning, ambitious, and self-seeking impostor.[14][186] Guillaume Postel was among the first to present a more positive view of Muhammad.[14] Boulainvilliers described Muhammad as a gifted political leader and a just lawmaker.[14] Gottfried Leibniz praised Muhammad because "he did not deviate from the natural religion".[14] Thomas Carlyle defines Muhammed as "A silent great soul, one of that who cannot but be earnest" [188]. Edward Gibbon in his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire observes that "the good sense of Mohammad despised the pomp of royalty." Friedrich Martin von Bodenstedt (1851) described Muhammad as "an ominous destroyer and a prophet of murder."[14] Later Western works, many of which, from the 18th century onward, distanced themselves from the polemical histories of earlier Christian authors. These more historically oriented treatments, which generally reject the prophethood of Muhammad, are coloured by the Western philosophical and theological framework of their authors. Many of these studies reflect much historical research, and most pay more attention to human, social, economic, and political factors than to religious, theological, and spiritual matters.[19].

It was not until the latter part of the 20th century that Western authors combined rigorous scholarship as understood in the modern West with empathy toward the subject at hand and, especially, awareness of the religious and spiritual realities involved in the study of the life of the founder of a major world religion.[19] According to William Montgomery Watt and Richard Bell, recent writers have generally dismissed the idea that Muhammad deliberately deceived his followers, arguing that Muhammad "was absolutely sincere and acted in complete good faith"[189] and that Muhammad’s readiness to endure hardship for his cause when there seemed to be no rational basis for hope shows his sincerity.[190] Watt says that sincerity does not directly imply correctness: In contemporary terms, Muhammad might have mistaken his own subconscious for divine revelation.[191] Watt and Lewis argue that viewing Muhammad as a self-seeking impostor makes it impossible to understand the development of Islam.[192][193] Welch holds that Muhammad was able to be so influential and successful because of his firm belief in his vocation.[14]

Other religious traditions

- Bahá'ís venerate Muhammad as one of a number of prophets or "Manifestations of God", but consider his teachings to have been superseded by those of Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahai faith.[194]

- Muhammad is regarded as one of the Saints of Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica.

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints does not regard Muhammad as a prophet, nor accept the Qur’an as a book of scripture. However, they do respect Muhammad as one who taught moral truths which can enlighten nations and bring a higher level of understanding to individuals.[195]

- Guru Nanak, a founder of Sikhism, viewed Muhammad as an agent of the Hindu Brahman.[196]

Criticism of Muhammad

Beginning in his own lifetime, and continuing to the present day, Muhammad has been the focus of criticism on a variety of subjects.[197][198][199]

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ See Muhittin Serin (1988)

- ↑ Unicode has a special "Muhammad" ligature at U+FDF4 ﷴ

- ↑ click here for the Arabic pronunciation.

- ↑ Variant transcriptions of Muhammad's name, besides those used above, include — (English and multiple European languages:) "Mahomet"; (French:) "Mahomet, Mohamed, Mouhammed, Mahon, Mahomés, Mahun, Mahum, Mahumet, Mahound (medieval French), Mohand (for Berber speakers), Mouhammadou and Mamadou (in Sub-Saharan Africa)"; (Latin:) "Machometus, Mahumetus, Mahometus, Macometus, Mahometes"; (Spanish:) "Mahoma"; (Italian:) "Maometto"; (Portuguese:) "Maomé"; (Greek:) "Μωάμεθ, Μουχάμμαντ, Μοχάμαντ, Μοχάμεντ, Μουχάμεντ, Μουχάμμαιντ"; (Turkish:) "Mehmet"; (Kurdish:) "Mihemed". See also Encyclopedia of Islam: (German:) "Machmet" (pre-20th century).

- ↑ The sources frequently say that, in his youth, he was called by the nickname "Al-Amin" meaning "Honest, Truthful" cf. Ernst (2004), p. 85.

- ↑ Elizabeth Goldman (1995), p. 63

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p. 12.

- ↑ Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 F. E. Peters (2003), p. 9.

- ↑ Alphonse de Lamartine (1854), Historie de la Turquie, Paris, p. 280:

"Philosophe, orateur, apôtre, législateur, guerrier, conquérant d'idées, restaurateur de dogmes, d'un culte sans images, fondateur de vingt empires terrestres et d'un empire spirituel, voilà Mahomet!"

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Encyclopedia of World History (1998), p. 452

- ↑ 'Islam' is always referred to in the Qur'an as a dīn, a word that means "way" or "path" in Arabic, but is usually translated in English as "religion" for the sake of convenience

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p. 12; (1999) p. 25; (2002) pp. 4–5

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 14.18 14.19 14.20 14.21 14.22 14.23 14.24 14.25 14.26 14.27 14.28 14.29 14.30 14.31 14.32 14.33 14.34 14.35 14.36 14.37 14.38 14.39 14.40 14.41 14.42 Alford Welch, Muhammad, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ "Muhmmad," Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 See:

- Holt (1977a), p.57

- Lapidus (2002), pp 0.31 and 32

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ann Goldman, Richard Hain, Stephen Liben (2006), p.212

- ↑ Watt (1974) p. 231

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Muhammad; Encyclopædia Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/396226/Muhammad.

- ↑ Jean-Louis Déclais, Names of the Prophet, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Uri Rubin, Muhammad, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ Ernst (2004), p. 80

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 S. A. Nigosian(2004), p. 6

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Watt (1953), p.xi

- ↑ Reeves (2003), pp. 6–7

- ↑ Donner (1998), p. 132

- ↑ Watt (1953), p.xv

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Lewis (1993), pp. 33–34

- ↑ Cragg, Albert Kenneth. "Hadith". Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9105855/Hadith. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ↑ Madelung (1997), pp.xi, 19 and 20

- ↑ Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs, 10th edition (1970), p.112.

- ↑ Watt (1953), pp.1–2

- ↑ Watt (1953), pp. 16–18

- ↑ Loyal Rue, Religion Is Not about God: How Spiritual Traditions Nurture Our Biological,2005, p.224

- ↑ John Esposito, Islam, Expanded edition, Oxford University Press, p.4–5

- ↑ See:

- Esposito, Islam, Extended Edition, Oxford University Press, pp.5–7

- Qur'an 3:95

- ↑ Kochler (1982), p.29

- ↑ cf. Uri Rubin, Hanif, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ See:

- Louis Jacobs(1995), p.272

- Turner (2005), p.16

- ↑ See also [Qur'an 43:31] cited in EoI; Muhammad

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Watt (1974), p. 7.

- ↑ Josef W. Meri (2005), p. 525

- ↑ Watt, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ↑ Watt, Amina, Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Watt (1974), p. 8.

- ↑ Armand Abel, Bahira, Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History (2005), v.3, p. 1025

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p. 6

- ↑ See for example Marco Schöller, Banu Qurayza, Encyclopedia of the Quran mentioning the differing accounts of the status of Rayhana

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Barbara Freyer Stowasser, Wives of the Prophet, Encyclopedia of the Quran

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p. 18

- ↑ Bullough (1998), p. 119

- ↑ Reeves (2003), p. 46

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 Watt, Aisha, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 D. A. Spellberg, Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past: the Legacy of A'isha bint Abi Bakr, Columbia University Press, 1994, p. 40

- ↑ Karen Armstrong, Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet, Harper San Francisco, 1992, p. 145.

- ↑ Barlas (2002), p.125-126

- ↑ Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:234, Sahih al-Bukhari, 5:58:236, Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:62:64, Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:62:65, Sahih al-Bukhari, 7:62:88, Sahih Muslim, 8:3309, 8:3310, 8:3311, 41:4915, Sunnan Abu Dawud, 41:4917

- ↑ Tabari, Volume 9, Page 131; Tabari, Volume 7, Page 7

- ↑ Momen (1985), p.9

- ↑ Tariq Ramadan (2007), p. 168–9

- ↑ Asma Barlas (2002), p. 125

- ↑ Armstrong (1992), p. 157

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Nicholas Awde (2000), p.10

- ↑ Ordoni (1990) pp. 32, 42–44.

- ↑ "Ali". Encyclopedia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Emory C. Bogle (1998), p.6

- ↑ John Henry Haaren, Addison B. Poland (1904), p.83

- ↑ Brown (2003), pp. 72–73

- ↑ Emory C. Bogle (1998), p.7

- ↑ See:

- Emory C. Bogle (1998), p.7

- Razwy (1996), ch. 9

- Rodinson (2002), p. 71.

- ↑ Brown (2003), pp. 73–74

- ↑ Uri Rubin, Muhammad, Encyclopedia of the Quran

- ↑ Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 31.

- ↑ Daniel C. Peterson, Good News, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Watt (1953), p. 86

- ↑ Ramadan (2007), p. 37–9

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 36.

- ↑ F. E. Peters (1994), p.169

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Uri Rubin, Quraysh, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ Jonathan E. Brockopp, Slaves and Slavery, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ W. Arafat, Bilal b. Rabah, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Watt (1964) p. 76.

- ↑ Peters (1999) p. 172.

- ↑ Muhammad Nasiruddin Al-Albani, Nasb al Majaneeq fil Radd 'Ala Qissat al Gharaneeq, 1996, pg.1

- ↑ The aforementioned Islamic histories recount that as Muhammad was reciting Sūra Al-Najm (Q.53), as revealed to him by the Archangel Gabriel, Satan tempted him to utter the following lines after verses 19 and 20: "Have you thought of Allāt and al-'Uzzā and Manāt the third, the other; These are the exalted Gharaniq, whose intercession is hoped for." (Allāt, al-'Uzzā and Manāt were three goddesses worshiped by the Meccans). cf Ibn Ishaq, A. Guillaume p. 166.

- ↑ Al-Albani, pg.1

- ↑ Shahab Ahmed, Satanic Verses, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ F. E. Peters (2003b), p. 96

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Moojan Momen (1985), p. 4

- ↑ Muhammad, Encyclopædia Britannica, p.9

- ↑ J. Schacht, Fiḳh, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Muhammad, Encyclopædia Britannica, p.11–12

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p. 482

- ↑ http://www.sacred-texts.com/journals/jras/1893-15.htm

- ↑ Sells, Michael. Ascension, Encyclopedia of the Quran.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 97.3 Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 39

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Esposito (1998), p. 17.

- ↑ Moojan Momen (1985), p. 5

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 175, p. 177.

- ↑ "Ali ibn Abitalib". Encyclopedia Iranica. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v1f8/v1f8a043.html. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Fazlur Rahman (1979), p. 21

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Lewis (2002), p. 41.

- ↑ Watt (1961), p. 105.

- ↑ John Kelsay (1993), p. 21

- ↑ Watt(1961) p. 105, p. 107

- ↑ Lewis (1993), p. 41.

- ↑ Rodinson (2002), p. 164.

- ↑ Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 45

- ↑ Glubb (2002), pp. 179–186.

- ↑ Watt (1961), p. 123.

- ↑ Rodinson (2002), pp. 168–9.

- ↑ Lewis(2002), p. 44

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 179.

- ↑ Watt (1961), p. 132.

- ↑ Watt (1961), p. 134

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Lewis (1960), p. 45.

- ↑ C.F. Robinson, Uhud, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Watt (1964) p. 137

- ↑ Watt (1974) p. 137

- ↑ David Cook(2007), p.24

- ↑ See:

- Watt (1981) p. 432;

- Watt (1964) p. 144.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Watt (1956), p. 30.

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 34

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 18

- ↑ Watt (1956), pp. 220–221

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 35

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 36, 37

- ↑ See:

- Rodinson (2002), pp. 209–211;

- Watt (1964) p. 169

- ↑ Watt (1964) pp. 170–172

- ↑ Peterson(2007), p. 126

- ↑ Ramadan (2007), p. 141

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 39

- ↑ [Qur'an 2:196-210]

- ↑ Lings (1987), p. 249

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 136.2 136.3 Watt, al- Hudaybiya or al-Hudaybiyya Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Lewis (2002), p. 42.

- ↑ Lings (1987), p. 255

- ↑ Vaglieri, Khaybar, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 Lings (1987), p. 260

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Khan (1998), pp. 250–251

- ↑ F. Buhl, Muta, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ 143.0 143.1 143.2 143.3 Khan (1998), p. 274

- ↑ 144.0 144.1 144.2 Lings (1987), p. 291

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 Khan (1998), pp. 274–5.

- ↑ Lings (1987), p. 292

- ↑ Watt (1956), p. 66.

- ↑ Rodinson (2002), p. 261.

- ↑ Harold Wayne Ballard, Donald N. Penny, W. Glenn Jonas (2002), p.163

- ↑ F. E. Peters (2003), p.240

- ↑ [Qur'an 110:1]

- ↑ Watt (1974), p.207

- ↑ M.A. al-Bakhit, Tabuk, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Lewis (1993), pp.43–44

- ↑ Watt (1974) p. 83

- ↑ Peterson (2006), pg. 86-9

- ↑ Devin J. Stewart, Farewell Pilgrimage, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ Al-Hibri (2003), p.17

- ↑ See:

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 The Last Prophet, page 3. By Lewis Lord of U.S. News & World Report. April 7, 2008.

- ↑ Leila Ahmed (1986), 665–91 (686)

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 F. E. Peters(2003), p.90

- ↑ "Isa", Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ See:

- Holt (1977a), p.57

- Hourani (2003), p.22

- Lapidus (2002), p.32

- Esposito(1998), p.36

- Madelung (1996), p.43

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p.35–36

- ↑ Cambridge History of Islam (1970), p. 30.

- ↑ 167.0 167.1 167.2 Lewis (1998)

- ↑

- Watt (1974), p. 234

- Robinson (2004) p. 21

- Esposito (1998), p. 98

- R. Walzer, Ak̲h̲lāḳ, Encyclopaedia of Islam Online

- ↑ Islamic ethics, Encyclopedia of Ethics

- ↑ Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 34

- ↑ Esposito (1998), p. 30

- ↑ Watt, The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 52

- ↑ 'Human Rights in Islam'. Published by The Islamic Foundation (1976) - Leicester, U.K

- ↑ see e.g. Al Azhar scholar Sheikh Abdul Majid Subh's writings

- ↑ Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya recorded the list of some names of Muhammad's female-slaves in Zad al-Ma'ad, Part I, p. 116

- ↑ Ali, Wijdan (1999),p. 3

- ↑ Farah (1994), p.135

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Encyclopedia Britannica, Muhammad, p.13

- ↑ 179.0 179.1 Denis Gril, Miracles, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ A.J. Wensinck, Muʿd̲j̲iza, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ↑ Daniel Martin Varisco, Moon, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an

- ↑ Stillman, Norman (1979).

- ↑ "Mohammed and Mohammedanism", Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913

- ↑ Göran Larsson (2003), p. 87

- ↑ Reeves (2003), p. 3

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 Lewis (2002) p. 45.

- ↑ Said, Edward W (2003). Orientalism. Penguin. p. 68. ISBN 0141187425, 9780141187426. http://books.google.com/?id=zvJ3YwOkZAYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=orientalism&cd=3#v=onepage&q.

- ↑ On heroes and hero worship by Thomas Carlyle

- ↑ Watt, Bell (1995) p. 18

- ↑ Watt (1974), p. 232

- ↑ Watt (1974), p. 17

- ↑ Watt, The Cambridge history of Islam, p. 37

- ↑ Lewis (1993), p. 45.

- ↑ Smith, P. (1999). A Concise Encyclopedia of the Bahá'í Faith. Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications. pp. 251. ISBN 1851681841.

- ↑ James A. Toronto (August 2000). "A Latter-day Saint Perspective on Muhammad". Ensign. http://www.lds.org/portal/site/LDSOrg/menuitem.b12f9d18fae655bb69095bd3e44916a0/?vgnextoid=2354fccf2b7db010VgnVCM1000004d82620aRCRD&locale=0&sourceId=bbaba1615ac0c010VgnVCM1000004d82620a____&hideNav=1. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Peter Teed (1992), p.424

- ↑ Stillman, Norman (1979). The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book, p. 236, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 0-8276-0116-6.

- ↑ http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/speeches/2006/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20060912_university-regensburg_en.html

- ↑ Slaughter And 'Submission' - CBSnews.com

References

- Ahmed, Leila (Summer 1986). "Women and the Advent of Islam". Signs 11 (4): 665–91. doi:10.1086/494271.

- Ali, Muhammad Mohar (1997). The Biography of the Prophet and the Orientalists. King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Qur'an. ISBN 9960-770-68-0. http://www.islamhouse.com/p/51772.

- Wijdan, Ali (August 23–28, 1999). "From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th century Ottoman Art". Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art (Utrecht, The Netherlands eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen.) (7): 1–24. http://www2.let.uu.nl/Solis/anpt/ejos/pdf4/07Ali.pdf.

- Armstrong, Karen (1992). Muhammad: A Biography of the Prophet. Harpercollins. ISBN 0062508865.

- Awde, Nicholas (2000). Women in Islam: An Anthology from the Quran and Hadith. Routledge. ISBN 0700710124.

- Ballard, Harold Wayne; Donald N. Penny, W. Glenn Jonas (2002). A Journey of Faith: An Introduction to Christianity. Mercer University Press. ISBN 0865547467.

- Barlas, Asma (2002). Believing Women in Islam. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292709048.

- Bogle, Emory C. (1998). Islam: Origin and Belief. Texas University Press. ISBN 0292708629.

- Brown, Daniel (2003). A New Introduction to Islam. Blackwell Publishing Professional. ISBN 978-0631216049.

- Bullough, Vern L; Brenda Shelton, Sarah Slavin (1998). The Subordinated Sex: A History of Attitudes Toward Women. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0820323695.

- Cohen, Mark R. (1995). Under Crescent and Cross (Reissue ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691010823.

- Dakake, Maria Massi (2008). The Charismatic Community: Shi'ite Identity in Early Islam. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791470334.

- Donner, Fred (1998). Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing. Darwin Press. ISBN 0-87850-127-4.

- Endress, Gerhard (2003). Islam. New Age Books. ISBN 978-8178221564.

- Ernst, Carl (2004). Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5577-4.

- Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511233-4.

- Esposito, John (1999). The Islamic Threat: Myth Or Reality?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513076-6.

- Esposito, John (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515713-3.

- Farah, Caesar (1994). Islam: Beliefs and Observances (5th ed.). Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0812018530.

- Glubb, John Bagot (1970 (reprint 2002)). The Life and Times of Muhammad. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-8154-1176-6.

- Goldman, Elizabeth (1995). Believers: spiritual leaders of the world. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195082400.

- Goldman, Ann; Richard Hain, Stephen Liben (2006). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198526539.

- Haaren, John Henry; Addison B. Poland (1904). Famous Men of the Middle Ages. University Publishing Company. ISBN 188251405X.

- Al-Hibri, Azizah Y. (2003). "An Islamic Perspective on Domestic Violence". 27 Fordham International Law Journal 195.

- Holt, P. M.; Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam (Paperback). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521291354.

- Hourani, Albert; Ruthven, Malise (2003). A History of the Arab Peoples. Belknap Press; Revised edition. ISBN 978-0674010178.

- Ishaq, Ibn; Guillaume, Alfred, ed. (2002). The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ibn Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0196360331.

- Jacobs, Louis (1995). The Jewish Religion: A Companion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198264631.

- Kelsay, John (1993). Islam and War: A Study in Comparative Ethics. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664253024.

- Khan, Majid Ali (1998). Muhammad The Final Messenger. Islamic Book Service, New Delhi, 110002 (India). ISBN 81-85738-25-4.

- Kochler, Hans (1982). Concept of Monotheism in Islam & Christianity. I.P.O.. ISBN 3-7003-0339-4.

- Lapidus, Ira (2002). A History of Islamic Societies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521779333.

- Larsson, Göran (2003). Ibn Garcia's Shu'Ubiyya Letter: Ethnic and Theological Tensions in Medieval Al-Andalus. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 9004127402.

- Lewis, Bernard (1993, 2002). The Arabs in History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280310-7.

- Lewis, Bernard (1992). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry (Reprint ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0195053265.

- Lewis, Bernard (January 21, 1998). "Islamic Revolution". The New York Review of Books. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/4557.

- Lings, Martin (1987). Muhammad: His Life Based on Earliest Sources. Inner Traditions International, Limited .. ISBN 0-89281-170-6.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521646960.

- Momen, Moojan (1985). An Introduction to Shi'i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300035314.

- Neusner, Jacob (2003). God's Rule: The Politics of World Religions. Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-910-6.

- Nigosian, S. A. (2004). Islam:Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253216273.